Boying was at the forefront of activists in medical school who studied and analyzed the Philippine health care system and found it wanting in light of the activist mantra “Serve the People”. He would take the path less taken when. After graduation, he first devoted himself to community-based health programs engaged in primary health care as well as arousing, organizing and mobilizing people at the grassroots, the masa, to struggle for substantial change in the larger socio-political arena.

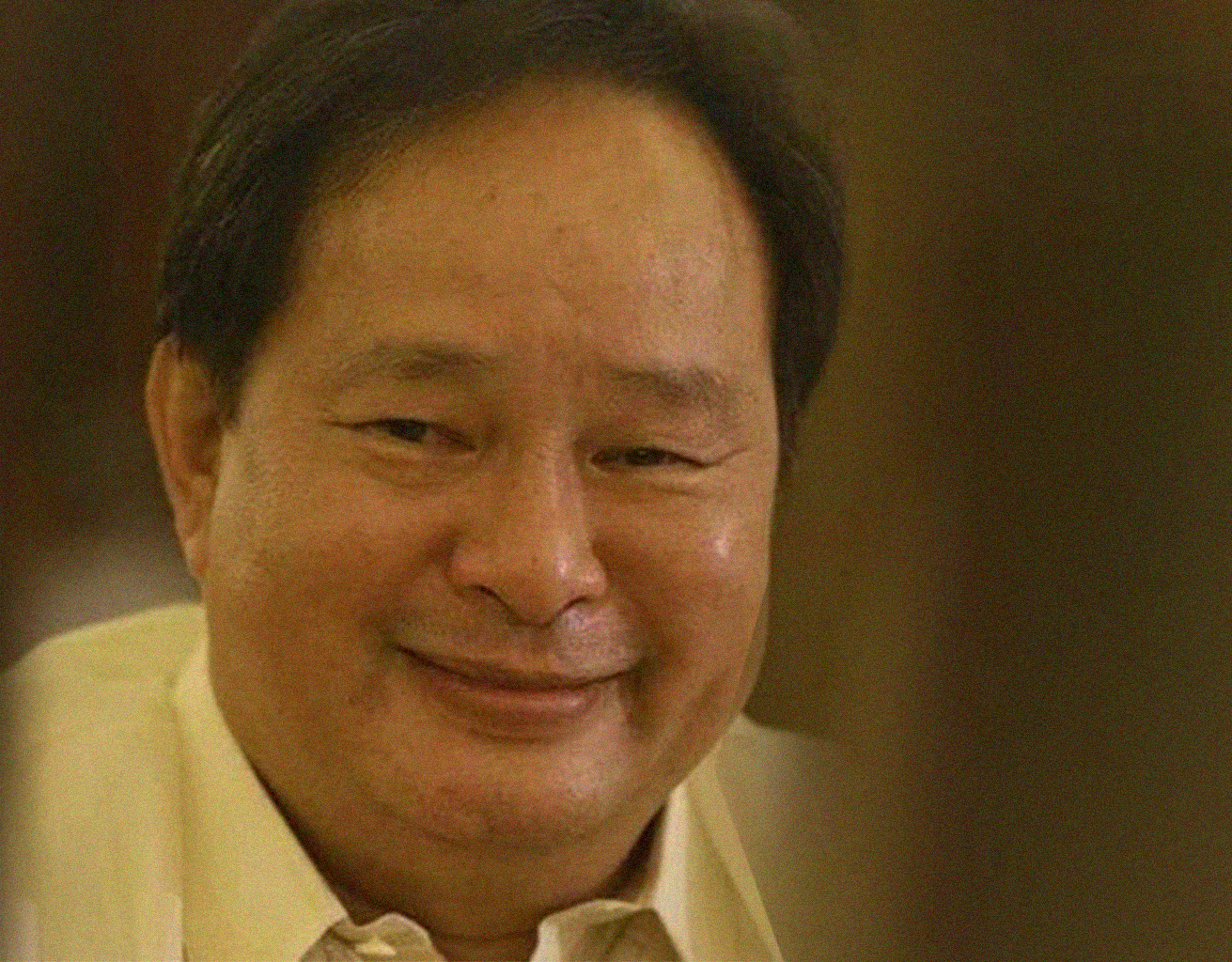

Aking parangal kay Dr. Daniel “Boying” de la Paz (November 20, 1954 – April 5, 2023)

(Mula kay Dr. Carol Pagaduan Araullo)

Magandang hapon sa lahat ng mga kaanak at kaibigan at kasamahan ni Boying lalo na sa kanyang walang kasing bait at matyagang maybahay na si Delen at kanyang mga anak — Miko, Tomi at Enzo.

Naatasan akong ipakilala sa inyo si Boying pero malamang kilala na niyo siya bilang ama, kaibigan at napakahusay na manggagamot. Ang maibabahagi ko ay ang pagiging progresibo niya, isang demokratiko at makabayang Filipino, isang aktibistang panlipunan at isang kakaibang manggagamot.

Boying came from an activist family of progressives. There was his elder brother Bobby, his much older half-sister, Alice, who they, and later we, called “Ninang”, his mother, Lydia, and his younger brother Benjie. Youngest sister, Baby, herself became a worker in a non-profit NGO. Boying was, philosophically, a student of Marx, Engels and Mao.

We got to be friends only in medical school, as I, delayed by 2 years because of a stint in Marcos’ detention camp a year after martial law, entered UPCM as part of Class 1979. He was a year younger than me, but oh so much older and wiser in ways I did not then realize.

He was an acknowledged leader by his batch of pre-Med students and so, was elected our class president. He had a better sense of how to hold together a class of 144 disparate individuals, the biggest batch thus far, than I, who at some point, out of impatience, brashly attempted to herd the class into some kind of decision making, and was promptly rebuffed. You see my years of political activism tried and tested in more antagonistic and tension-filled circumstances just was not appropriate, and did not work, among excited, anxious and a bit tempestuous first-year medical students. Boying’s calm, kindly, and patient demeanor plus his big, huggable bear exterior worked every time.

I always wondered how he got away with always playing tennis with mates Alex and Manny, the Tuazon non-brothers, have several ongoing extra-curricular activities and still seem to be always in non-panic mode before our non-stop, grueling exams in Anatomy. When it was time for Biochemistry and Physiology, while we fact-guzzling classmates frenziedly quizzed each other 10 minutes before exams about numerous details, he would ask us to answer an essay-type question that required analysis and not just memorization. He was exasperating in that way.

Boying and several of us activists in the class would spend down time doing medical missions in Tondo slums, mingling with ordinary poor folk, our future patients at PGH. During summer breaks, we would spend several weeks among lambanog-drinking coconut farmers in Quezon, singing at haranas in the barrios and for me — displaying my ignorance about handwashing clothes at the river bank for all the experienced launderers among the womenfolk to witness and laugh at.

It was our way of keeping ourselves grounded, who were we going to serve as doctors, how we would break from the standard mold of urban-centered, hospital-based, specialty focused clinical practice, most likely outside the Philippines.

For Boying was at the forefront of activists in medical school who studied and analyzed the Philippine health care system and found it wanting in light of the activist mantra “Serve the People”. He would take the path less taken when. After graduation, he first devoted himself to community-based health programs engaged in primary health care as well as arousing, organizing and mobilizing people at the grassroots, the masa, to struggle for substantial change in the larger socio-political arena.

Boying was also keenly aware that medical and paramedical students as well as professionals needed to be awakened to the injustices, inequities and outright horrors taking place under the US backed-Marcos dictatorship so that they could add their voices to its overthrow while providing needed health services to its victims and to those fighting life-and-death battles against it. He was a founding member of the first health human rights group, an alliance for national democracy in the health sector and beginning efforts in organizing hospital workers.

Boying found a kindred spirit in Delen, the pretty, bubbly and unpretentious med student a year below us. He even brought me to her class once, before he actually embarked on courting her. Para tulungan siya kilatisin. Syempre two thumbs up ako.

Boying spent his rural health practice in Samar where his older brother Bobby had established a thriving practice, if not in monetary terms, but certainly in terms of number of patients among the poorest of the poor. Most of our group of activists chose the Cordilleras instead, it being more accessible to kith and kin, yet still with many underserved communities particularly among indigenous peoples. I know he was disappointed that we didn’t join him in Samar but he forged ahead by himself.

Boying would probably have chosen a similar path to Bobby were it not for the tragic murder of his brother by the military upon unfounded accusations that he was ministering to the New People’s Army. For that was the immediate conclusion when the military saw UP graduates giving health services to far flung communities of the underserved and under privileged. Our Cordillera group doing rural practice received the same kind of suspicious reception but fortunately did not stay long enough in the areas to merit being in the military’s deadly cross hairs.

At some point after Bobby’s killing, Boying decided to do surgical residency. While no longer in the preventive, promotive, primary health care area of practice, his decision was accepted and eventually welcomed by us since the need for competent, caring and committed physicians at the secondary and tertiary levels could not be denied.

Boying proved to be such and much more. It need not be said that he was unstinting in providing his services to those who needed them, whether fellow activists, ordinary folk who could not afford expensive medical care, co-workers in the hospital with limited budgets, and a plethora of referrals from wherever who had heard of this kind, understanding and accessible doctor.

And Boying was a physician, a healer, in the best tradition. He saw his patient in his or her entirety, not just a sick or malfunctioning part or organ. He saw the whole person including what were his or her psycho-social circumstances and conditions that impinged on the patient’s ill health and the road to wellness.

I was Boying’s patient many times over and therefore I can attest to this from personal experience. He helped me sort out the confusing and contradictory options for managing my cancer. He continued to do the same, helping me to consider calmly and rationally, what was needed to be done for other patients whose cases I referred to him. For Boying was analytical, methodical, practical as well as, refreshingly philosophical, always trying to show the bigger picture.

One can be a bit awed by Boying, kasi nga magaling at mabilis siya makaamoy ng kalokohan. But even as he could read people’s not so noble intentions and baser motives, he tried to understand where they were coming from, he tried to accommodate them, even as he was not one to easily fall for manipulative schemes.

For as long as he knew you were trying to be honest, even self-critical, magkakaintindihan kayo. And for this I will always be grateful, na nagkakaintindihan kami. Kaya niyang itulak ako na maging makatotoo, set aside false pride and self-defensiveness, and get to the bottom of things. I think to some extent, I also had a similar effect on him.

Paalam mahal na kaibigan, kasama, kaklase. I am happy you are resting now albeit we will miss you terribly. Rest in peace, you more than deserve it.