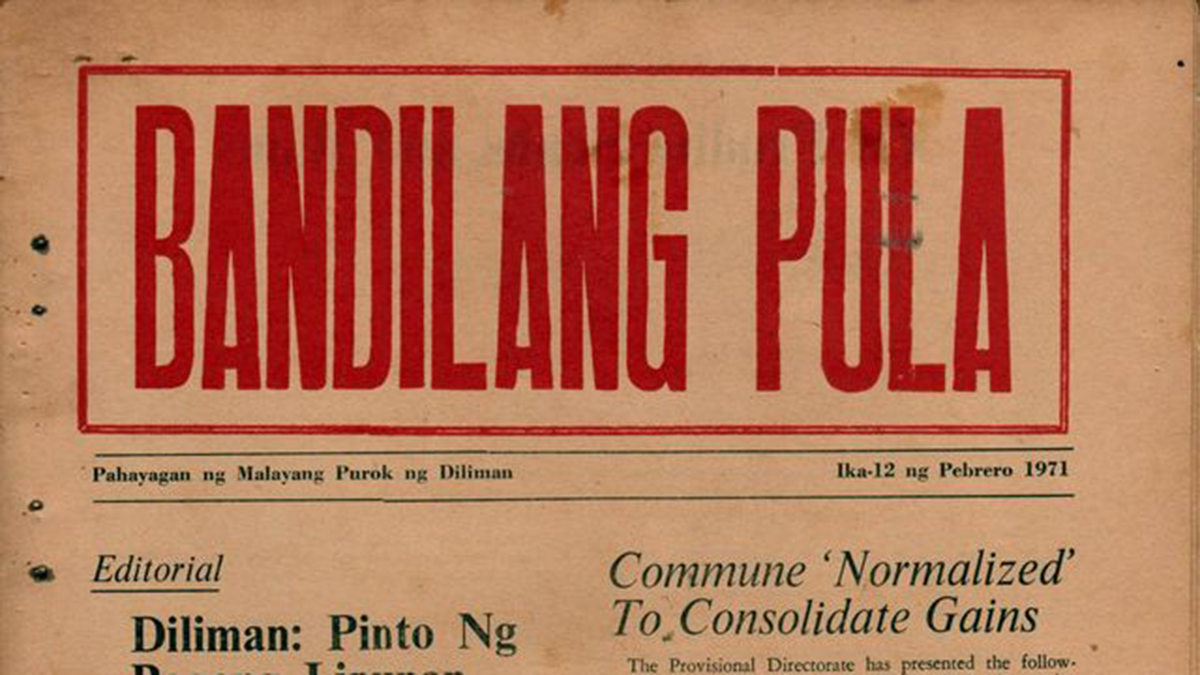

These are scans from Monram’s own copy of the Bandilang Pula, a publication during the 1971 Diliman Commune. Engr. Mon Ramirez also scanned and OCR’d parts of this publication. Sharing some of the OCR’d content here.

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE 3RD DAY OF THE DILIMAN COMMUNE, FEB 3

- Students strengthened the various barricdes and set up more. There was virtual takeover of Palma and Melchor Halls where red flags were hoisted on top. The Philippine flag atop Quezon Hall had its red side up.

- An assembly, called by UP President Salvador P. Lopez, was held at the steps of Palma Hall at at 11AM. He spoke on two issues: the “militarization” of the University and the proposed closure of the University.

- Police re-entered the campus while the assembly was going on. A group of UP officials walked the Beta Way to meet the head of the police column in front of Melchor Hall. The police agreed to withdraw. Nevertheless, around 4 PM skirmishes between the police and barricaders occurred in the vicinity of Vinzons Hall.

- In the early afternoon, some senators arrived: Kalaw, Salonga, Benitez, Aquino, tamano, Magsaysay, Laurel, Lagumbay and Tañada. They conferred with the UP Pres. Lopez who telephoned Marcos to urge him to remove the troops so that the community can solve the problem of the barricades. Marcos agreed on condition that President Lopez would assume responsibility for the situation. The troops were withdrawn in the late afternoon.

- All the while the students continued their broadcast over DZUP which was taken over a day earlier, on the second day of the Diliman Commune.

- Students broke into the UP Library and found their way to the roof to post lookouts.

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE 4TH DAY OF THE DILIMAN COMMUNE, FEB 4

- The barricaders formed and announced the “Provisional Directorate of the Diliman Commune” composed of the following: a faculty representative, two representatives from the students, a representative each from Area 11 and Barrio Krus na Ligas. The barricaders had invited Pres. Lopez and Dean Majul the previous day to the Directorate to represent the Administration but he did not agree.

- The students took over the UP Press in the afternoon and printed “Bandilang Pula” with the help of the UP Press technicians.

- Pastor Mesina, Jr., the student gunned down by Math Prof Inocentes Campos on the first day of the barricades, passed on in the evening at the Veterans Memorial Hospital.

- The UP administration organized a community Working Committe to establish rapport with the students. It was chaired by Dean Malay and had for members the follwoing: Dean Majul, Dean Escudero, Professors Zeus Salazar, Roger Posadas, Virginia Agbayani, Temario Rivera, and four more. A counterpart number of students were to be named by the UP University Student Council Chair.

Radio Diliman Libre

Among the 8 basic demands presented by the Provisional Directorate in the name of the students and other sectors of the University during the period of the barricade mass actions, were those referring specifically to the DZUP radio facilities and the University Press.

It is extremely necessary to be clear with respect to these demands and their significance in the context of the national democratic cultural revolution being waged by all progressives inside and outside the campus.

Previous to the period of activist occupation, the DZUP was nothing more than a literally provincial radio station, with a very limited radius of operation, content with playing over trivial and childish programs and even ready-made USIS tapes. The rest of the time was devoted to an equally trivial and sterile use of the radio by Speech associations. Fortunately, we hope that we shall be spared the unbelievable shallowness of its barely anecdotal existence from now on.

The UP Press was, previous to activist occupation, no different. The UP Press was devoted to the publication of registration programs, invitations and meal tickets, or, with regards to book publication, outside of several exemptions (such as the writings of Agoncillo or Daroy) its gallery was characterized by mediocrity, pedantry and passionate irrelevance (such as those on poultry raising or an extremely involved scientific dissertation of mosses and ferns, and the “scholarly” mendicant writings of Alex Fernandez).

The takeover of the DZUP radio last Wednesday and of the University Press the following Thursday opened up completely new uses and potentialities of these facilities.

Overnight, the DZUP became the liberated voice of the democratic commune, and the UP Press—through its initial issue of the Bandilang Pula—became the liberated Word of the militants.

Together, these resources managed by the students, besieged by fascist forces and yet protected by the barricades, began to take concerted means to give form and articulation, density and firmness to the daily struggle and life of the beleaguered Commune. Through every strategic barricade, room and rooftop and to every group and every individual ear, Radio Free Diliman weaved a solidarity both constantly surprising and unmatched in its vigor and militance. Both radio and the published word not only discussed and clarified the issues involved in the barricade action, but also exposed saboteurs and enemies of the mass actions (such as the MPKP and the Puno bandits); warned of incoming fascist forces, coordinated defenses and food supply; announced meetings, called for and heartily acknowledged contributions and aid to the students and endlessly exhorted for an increasing vigilance from the ranks of the militants.

Thus Radio Free Diliman was actively on the air for an average of 20 hours daily (twice the transmission tubes i burned out due to continued use and once an anonymous source promptly donated the necessary spare part costing hundreds of pesos). Meanwhile, the fascist state continually attempted to jam the Radio of Liberation.

In response to the students militance and call for popular support, the voice of liberated Diliman, was closely listened to by large sectors of our society and, nor in the least, by workers and peasants in provinces such as Bulacan, Laguna, Quezon and—thanks to an anonymous supporter who relayed the broadcasts–as far as Palawan.

Representatives of numerous groups and organizations —students, faculty members, residents, workers, peasants, jeepney drivers and fishermen—came to speak, freely and with utmost candor, to each other and to their progressive allies. They spoke of their demands, the problems, their anger, but above all, of the increasing unity and consciousness of these violated classes and sectors of our wretched society.

At the very height and intensity of the barricade actions —particularly last Tuesday and Wednesday—with sheer courage and spontaneity, the large number of students discovered the multiple bonds which held them together. The struggle testified to the unity of students, faculty residents, workers and peasants.

The militant and courageous Diliman Commune exhibited, in actions which will remain historic in their eloquence, the microcosm of the problems and the developing forces of Philippine society.